WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump may be attempting to tackle drug trafficking by killing purported smugglers, but the Colombian military says it’s looking to a more creative solution: killing the high.

“We are investigating one chemical form, chemical molecular, to put inside of the fuel in order to affect the composition of the cocaine,” Colombia’s Minister of Defense Pedro Sánchez told Breaking Defense during an interview in late 2025. The hope is to diminish cocaine’s potency, kneecapping its global demand.

“If you make the invention, I’ll give you $1 million,” he later quipped.

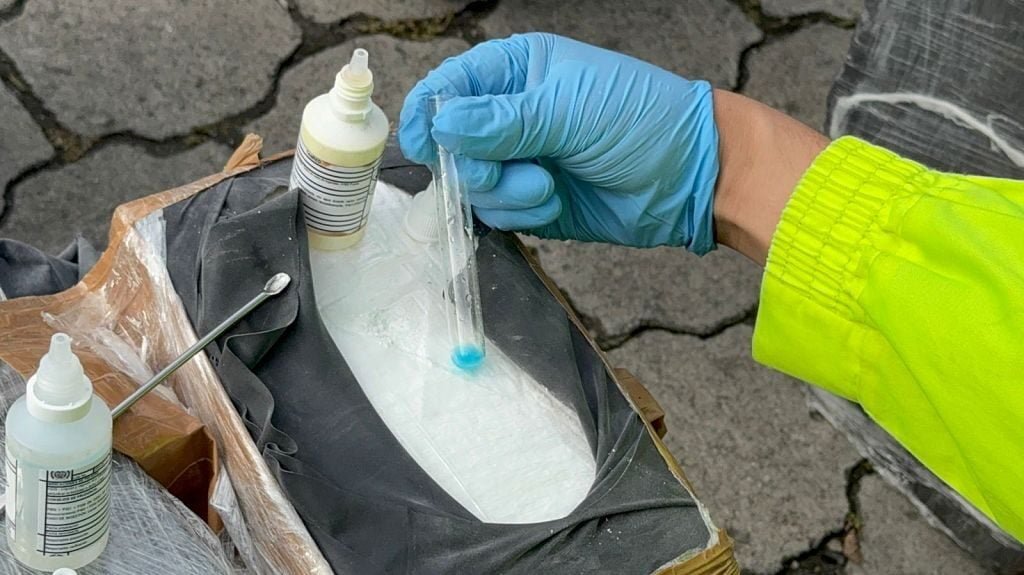

During cocaine production, after coca leaves are harvested, they are soaked in gasoline or a similar fuel, which acts as a solvent. Once the fuel absorbs the coca alkaloid, the plant matter is discarded, leaving a liquid that contains the extracted substance. That liquid then undergoes a chemical separation causing the coca extract to solidify, producing a crude paste. The paste is then transferred to a lab where impurities are removed and the substance converted into cocaine powder for export.

The Colombian government, Sánchez explained, is actively working with universities inside the country, as well as companies and “anybody in this world” to see if there is a viable way to modify the nation’s gasoline supply to ultimately make cocaine less potent. The gambit recalls a reported secret decade-long CIA operation to similarly sabotage Afghanistan’s opium production.

While Sánchez did not disclose specifics of where the hunt stands, he said the plan is to start testing out different options soon, and an aide confirmed last week that such testing is now underway.

But even if the Colombian government is able to find a way to modify gasoline and funnel it throughout the country, the former general said the challenge will be making sure there aren’t easy workarounds like modifying coca plants.

“Maybe they produce a stronger coca,” Sánchez added. “That is the problem necessary to find … [to make sure] the coca doesn’t work.”

The effort comes at a tense geopolitical moment for Colombia, as Trump has embarked on a lethal campaign against drug trafficking into the US, including killing Colombian citizens that the US claims were smuggling drugs, sparking public outcry in Bogota.

For decades, the two countries have worked together, including during a key point in the counter-drug war of the 1990s when the US assisted the Colombian operation that killed drug kingpin Pablo Escobar. In 2022, Colombia was named, and officially remains, a major non-NATO ally to the US.

But despite that history of collaboration between the US and the Colombian military and National Police to combat coca production and flow of cocaine abroad, stats show supplies of “Colombian marching powder” on the uptick. In 2024, for example, the South American country was identified by the Drug Enforcement Administration as the primary source of US-seized cocaine [PDF]. After a May 2025 Congressional Research Report noted that coca cultivation there has continued to increase and in September 2025, Trump decided to add the South American country to a list of “major drug transit or major illicit drug producing countries.”

Some of the figures have funneled into the second Trump administration’s sizable chunk of its first year talking about the flow of drugs into the US, striking vessels in the western Hemisphere and rolling out a new National Security Strategy that calls for a revival of the Monroe Doctrine — essentially an 1823 US policy telling European powers to stay out of the Western Hemisphere.

They have also amplified public fighting, at times between Colombian President Gustavo Petro and Trump. For example, after Petro accused the US of killing a Colombian fisherman in a Sept. 16, strike on a vessel, Trump responded by calling the Colombian president “an illegal drug leader” and vowing to immediately stop all US payments and subsidies to Colombia.

Then in the wake of the early January US military operation capturing Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, Trump threatened military action against Petro’s government, telling reporters that such an operation “sounds good to me.” Shortly after, on Jan. 7, the Colombian Embassy in Washington, DC, released a statement saying that Bogota remains “committed to open dialogue and constructive engagement” with its ally.

Breaking Defense spoke with Defense Minister Sánchez in November, prior to the Venezuela operation. As for defense relations during the boat strikes at the time, at least at that time Sánchez maintained that “nothing” had changed in the US-Venezuela military-to-military relationship. If anything, he wished to “increase” cooperation in areas like protecting military installations and police facilities from the increased threat of drones used by cartels.

Last week the Colombian embassy did not respond to additional questions about mil-to-mil relations with the US, in a Jan. 16 Instagram post, Sánchez dubbed the relationship between the two countries as “strategic, strong, and long-standing.”

“We will continue to strengthen our cooperation on security, defense, and the fight against transnational crime,” he added. “Protecting democracy and hemispheric stability is a shared interest of our nation.”