Editor’s Note: This is a new occasional series brought to you by War on the Rocks. If you would like to pitch your own version, please refer to the contact information and guidance on our submissions page.

Wars very often inspire great American literature about the experience of war and its legacies — think of Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, or Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. We are fortunate now to be living through a great renaissance of veteran writing of policy analysis, memoir, poetry, and prose literature. All three of the works I’ve selected were written by veterans, two by veterans of our twenty-first century wars. At a time when our country requires a military comprised of just one half of one percent of our population, veteran sensibilities can make meaningful for the rest of us the costs and conduct of our wars. These three writers brilliantly engage the experience of war for individuals who fight them on our behalf. As Colum McCann writes in the introduction to the collection of short stories Fire and Forget, “The war went literary. And the literature broke our tired hearts.”

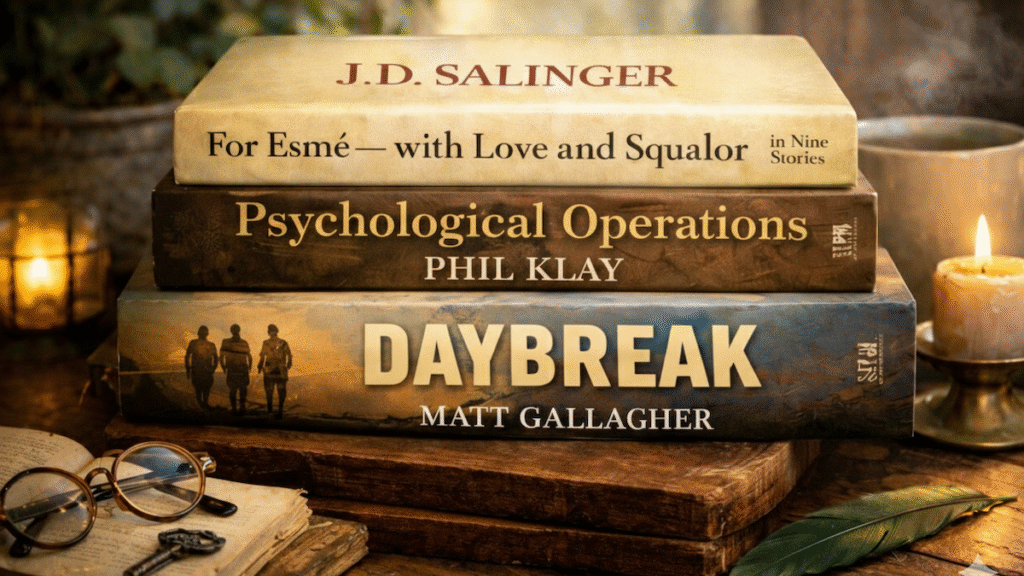

“For Esmé — with Love and Squalor,” by J.D. Salinger, in Nine Stories

Soldiering is central to Salinger’s art; his own World War II service was “the transformative trauma of his life and career.” He landed at Utah Beach on D-Day and was in the 4th Infantry Division at the Battle of the Bulge. He later suffered a nervous breakdown, just as the soldier does in “For Esmé.”

The narrator is wry, performatively perspicacious. In justifying the letter he sends as a wedding present to the girl who saved him, he begins, “If my notes should cause the groom, whom I haven’t met, an uneasy moment or two, so much the better.” But as with all the Glass family who comprise the characters of his interconnected work, the humor is a defense against despair. The tale the veteran recounts in the letter (she’d asked him to write her a story) is one of psychological shattering and salvation. The bride to whom the letter is addressed was a brave little girl who saved him with a sacramental offering that pulled him back into the living world.

An intelligence officer, bored and restless in England during the run up to the Normandy landings, goes to listen to a children’s choir and strikes up conversation with an extraordinary little girl (extraordinary children being a Salinger affliction), who professes an interest in squalor. He describes Esmé during choir practice as having “blase eyes that, I thought, might possibly have counted the house.” She wears a man’s military issue watch that belonged to her father, already killed serving in the war. The officer recounts the conversation:

[Esmé states,] “Father said I have no sense of humor at all. He said I was unequipped to meet life because I have no sense of humor.”

Watching her, I lit a cigarette and said I didn’t think a sense of humor was of any use in a real pinch.

“Father said it was.”

This was a statement of faith, not a contradiction, so I quickly switched horses. I nodded and said her father had probably taken the long view, which I was taking the short (whatever that meant).

As they part, she asks if she could write to him, saying “I hope you return from the war with all your faculties intact.”

He does not. Five campaigns after D-Day, he suffers a nervous breakdown. Unable to read, unable to sleep or bear bright lighting, he trembles and twitches and chain smokes to deal with the way “abruptly, familiarly and, as usual with no warning, he felt his mind dislodge itself and teeter, like insecure luggage on an overhead rack.”

What calms him, makes possible his recovery, is receipt of a letter from Esmé, enclosing her father’s watch. She offers it as “a lucky talisman.” That act of generosity, a near stranger giving him something they treasured to strengthen him as he fought to preserve their way of life, reclaims him. And it is his wedding gift to her, that child now grown, to tell her that she saved him.

What I love about this story is the portrait of soldiering: the casual way it describes the conversations among soldiers (“Clay left his feet where they were for a few don’t-tell-me-where-to-put-my-feet seconds”), the haunted feel of occupied Germany, well-meant but trifling and wholly uncomprehending correspondence from home, and the interior monologue and physical sensations of a mind untethered by strain. The story unapologetically accepts all of the above as an inherent part of warfare.

Esmé’s act of grace, in a story that is untainted by religion, serves as salvation. Because religion is the thrumming undercurrent in all of Salinger’s writing, but in “For Esmé” it is not yet freighted with religiosity. It is the human act of sacrament that provides salvation.

“Psychological Operations,” by Phil Klay, in Redeployment

I could pick any of the stories in this National Book Award-winning collection by Phil Klay. But I pick “Psychological Operations” because I think no one who wasn’t a veteran would have written it. It deals with the difficulty of explaining your experience of war to Americans who are living so securely far from it, and the yearning to be able to be honest about that experience, to reconnect with the society you defended.

The narrator is a veteran using his G.I. Bill benefits for an education to clamber into the middle class. The story opens with him describing a student he’s interested in: “Everything about Zara Davies forced you to take sides.” Neither are white, a rarity on campus, but she is a child of privilege, while he is further anomalous because of his military service. “It’s amazing how well the veteran mystique plays, even at a school like Amherst, where I’d have thought the kids would be smart enough to know better … everyone assumed I’d had some soul-scarring encounter.”

She converts to Islam, which she loves for the Ummah and the beauty of the Quran. To him, a Christian whose family came from Egypt, it is the violence of jihad. Zara seeks him out to talk about the war, asking, “How could you kill your own people?” He makes a tart reply, which she reports as threatening, an honor code violation that could have him expelled. So he chooses to play the post-traumatic stress card, and it works to avoid official censure.

Zara also apologizes when they are alone, which ignites his self-loathing. “‘You think the big bad war broke me,’ I said, ‘and it made me an asshole. That’s why you think I said those things. But what if I’m just an asshole?’” It’s such a powerful admission that society is ascribing to him an identity that, while beneficial, isn’t truly who he is. It’s just who we’re comfortable boxing him in as.

The title of the story comes from his occupational specialty, and is such a fine description of the manipulation he engages in. But what makes the story exceptionally moving is that the argument spurs honest engagement between them about his genuine experience of the war, and that is the center of gravity in the story.

He describes his missions in Fallujah and being with Marines as they went “100%,” each Marine in the unit having killed someone. She states her belief that civilians were innocents, rebutting his explanation that the U.S. forces were trying to persuade imams not to send “an untrained kid against a Marine squad in camouflaged positions with marked fields of fire” by justifying Iraqis fighting against invaders.

He admits he joined the Army to get to college. They compare her modest dress since conversion to a military uniform: a symbol of commitment. They talk about what it was like, him being an Arab American in the Army, she saying, “I don’t know if I could fight for an organization that treated me like that,” and he frustrated that she smugly can’t understand the unifying ethos of the military.

At his most honest he thinks:

I didn’t know if she’d understand. Or rather, if she’d understand it the way I did, which is what I really wanted … The weird thing about being a veteran, at least for me, is that you do feel better than most people. You risked your life for something bigger than yourself. How many people can say that? You chose to serve. Maybe you didn’t understand American foreign policy or why we were at war. Maybe you never will. But it doesn’t matter. You held up your hand and said, “I’m willing to die for these worthless civilians.”

At the same time, though, you feel somehow less. What happened, what I was a part of, maybe it was the right thing. We were fighting very bad people. But it was an ugly thing.

That’s about the most direct and honest description of people who volunteer for military service.

He’s yearning for connection, so he tells the worst part of his experience, of the degrading taunting of a jihadist knowing it would get them to attack. He expects her to flare in disgusted anger, but she proves worthier, superior even, by replying that she’s glad he’s able to talk about it and perhaps they’ll talk another time. Turns out this, too, is a war story about being given a human sacrament. In this case, it’s understanding.

Daybreak, by Matt Gallaher

Many of our best contemporary veteran writers are shape shifters, working in many forms, and none more so than Matt Gallagher. He burst onto the scene writing a blog during his deployment in Iraq that became the book Kaboom, wrote short stories and edited a book of other emerging veteran writers, and took up novels. I’m cheating a little, sneaking a recent novel into the novella category, but feel justified because it picks up a theme of other veterans of recent American wars (including Phil Klay with Missionaries): longing for a war that was meaningful to their society.

Daybreak is a love story, in several ways. It’s a man adrift, looking to redeem the mistakes he made in combat a decade ago, searching for a woman he loved, and wanted to join a war of moral clarity that his own war lacked. Mostly, though, it’s a love story about the people of Ukraine fighting to preserve their society. Gallagher volunteered in Ukraine, and it shows in his specificity about how Ukrainians are weathering the conflict: some as criminals, many as soldiers, most just trying to hold their lives and families together. They argue among themselves about who is contributing enough to the war effort. And he lets the Ukrainian characters speak for themselves. Grace at a dinner is, “Any act of normalcy is an act of courage. For that, we thank you.”

Gallagher captures so deftly the purposelessness many veterans feel returning to civilian life after the intensity and camaraderie of war, especially when so few of their countrymen have been in service. Being an army at war, not a country at war, rattles through the American’s experience of dislocation:

“Boy goes to war to become a man and comes back someone he doesn’t know,” Pax thought, “to a country he doesn’t recognize.” The biggest cliché on the fucking planet. The least I can do for anyone is keep it to myself.

The protagonist joins a group of volunteers going to Ukraine, only to realize how little he has to contribute. “Pax knew the only way to be someone again, was to come here, now, like this.” But he doesn’t make the cut to serve in Ukraine’s military. “Pax was thirty-three years old and certain his best days were already gone. This had been his chance. Now he had nowhere to go but the tunnels of infernal memory.”

But he finds redemption. He doesn’t find love with the women he was hoping to reconnect with. He finds it in a clarifying confrontation with his former commander from Afghanistan. He finds it in becoming useful as a mechanic, and in sacrifice. He goes to the front to retrieve his love’s wounded husband. He never really does figure himself out, and his death is inconsequential in a war of many consequential losses. But his dying sacrament is hearing her say, “You are good, Luke, and you are safe.”

What all three of these beautiful, poignant stories have in common is the search for meaning in the violence and displacement, human strength and human frailty, that war is an arbiter of. All three stories are of veterans needing to be reconnected when they are mired in loneliness because of their wartime experience. Salinger’s soldier becomes re-tethered by a stranger’s generosity. Klay’s soldier is unburdened by telling his story truthfully to the only person whose understanding he wants. Gallagher’s marine is lost until he makes himself useful to people with greater needs than his own. They are all war stories that are not about combat but about how to retrieve our veterans from the isolation of their experience.

Kori Schake leads the foreign and defense policy team at the American Enterprise Institute.

Image: Gemini